…From refugee camps to rural villages, young people fight for dignity, rights, and access to healthcare.

In a crowded Rohingya refugee camp, a young girl sat quietly, afraid to tell anyone that her body had changed. She had started her period but did not understand what was happening. There were no lessons in school, no books, and no one to explain. Even the word “menstruation” is whispered in shame.

Recalling, a Rohingya women’s rights advocate, Fatima Noor, “For many of us, health and wellbeing are not delayed rights, they are denied rights. Most refugee girls grow up without knowing how their bodies work. Pregnant women often go through nine months without ever seeing a doctor.”

Noor’s story shows the painful truth: while world leaders talk about gender equality and health, millions of young people, refugees, girls in villages, youth with disabilities, and those who are transgender, are left out. Promises under the global goals on health and equality sound good, but the reality for many young people is still filled with stigma, silence, and struggle.

In Uganda, Monalisa Akintole who is the country’s National Transgender Forum, lives a different but equally painful reality. As a young transgender advocate, she spends her days pushing for healthcare that respects her community. Yet instead of being welcomed, she often feels invisible.

“We are tired of systems and governments that kill youth who do not fit into the gender binary,” Akintole said firmly. “If you are not going to stand with me, please do not invite me to spaces where you only want to use me as a token youth.”

Her words cut deep. Like many other young transgender people, Akintole knows what it feels like to be invited to the table but not truly heard. She and her peers live with fear, stigma, and rejection, even when they are only asking for basic dignity and healthcare.

Noor and Monalisa’s experiences reflect a larger crisis. Despite global progress on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), many young people, especially adolescents, girls in rural areas, LGBTQ+ youth, indigenous groups, refugees, and those with disabilities, are still shut out of dignified, stigma-free healthcare.

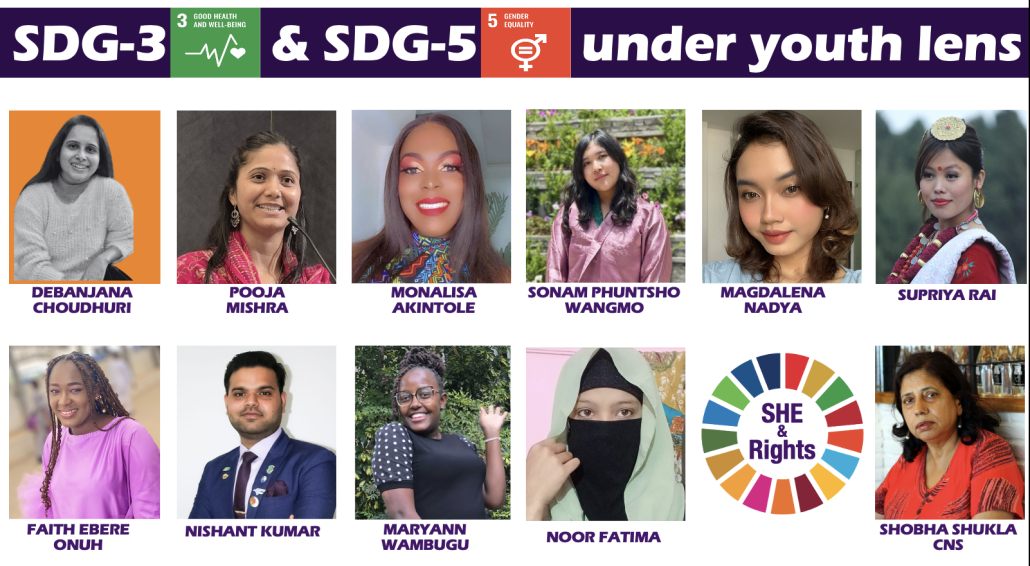

This painful gap was at the center of discussions at the SHE & Rights (Sexual Health with Equity & Rights) media brief , where young leaders from across the world raised their voices for change, calling for urgent action to bridge the gaps between gender equality, youth sexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR), and access to dignified healthcare.

The session co-hosted by several international organizations, including the Global Center for Health Diplomacy and Inclusion (CeHDI), Y+ Global, Asia Indigenous Youth Platform (AIYP), International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights (WGNRR), and CNS, on the sidelines of the International Conference on Family Planning (ICFP) 2025.

Speakers drawn from Asia, Africa, and refugee communities painted a worrying picture: young people continue to face taboo, stigma, criminalization, and systemic neglect. While policies exist, implementation is weak, funding remains inadequate, and marginalized groups are still invisible in decision-making.

The Executive Director of the Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights (WGNRR), Debanjana Choudhuri said that in the last decade there has been a considerable change in how young people are being addressed in sexual and reproductive health and rights,

“But it is still miles away from where they get mainstreamed,” said Debanjana Choudhuri, Executive Director of the Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights (WGNRR).”

According to her, safe abortion services, a critical component of SRHR, remain out of reach for many youth due to stigma and legal restrictions. “When a young person seeks abortion services, they are often stigmatized, creating an unsafe and vulnerable situation,” she added.

In the Philippines, WGNRR’s “Generation Change Makers” are challenging laws that criminalize abortion and comprehensive sexuality education (CSE).

They host community dialogues to bust myths and push for reforms. But in many parts of the Global South, CSE is still reduced to a single biology lesson.

“Young people must learn about consent, bodily autonomy, and choice early in life to make informed decisions,” Choudhuri stressed.

In Indonesia, the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), Magdalena Nadya, observed that while policies exist, stigma and legal barriers persist, especially for rural girls and young people with disabilities. “Progress on gender equality is stagnating. Early marriages, adolescent pregnancies, and gender-based violence remain widespread,” she said.

She emphasized that young people must not only be recipients of comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) but also co-designers, leveraging digital platforms to make SRHR education more relatable.

Choudhuri lamented that “In most of the countries in the Global South, comprehensive sexuality education is not available in schools. At times, it is reduced to one biology class. We need to talk about CSE from school level to ensure young people know about consent, bodily rights, bodily autonomy, and choice so they can make informed decisions.”

Supporting her view, Magdalena Nadya of IPPF East and South-East Asia and Oceania said: “We have to strengthen comprehensive sexuality education and access to SRHR services. Policies alone are not enough. Young people are not just recipients of CSE, they are also co-designing and co-facilitating it whether in classrooms or on social media. These campaigns make SRHR education more relatable and accessible.”

But she warned that inequalities persist: “For many, especially girls in rural or conservative areas, young people with disabilities, or indigenous youth, access is still limited. Progress on gender equality (SDG-5) has largely stagnated, with early marriages, adolescent pregnancies, gender-based violence, and female genital mutilation still prevalent.”

In Nigeria, Y+ Global and Gender Equality Fund Ambassador, Faith Ebere Onuh

criticized poor government funding for health.

“The UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Report shows the biggest number of maternal deaths worldwide happened in Nigeria (28.7%). Yet Nigeria invests just 5% of the national budget in health. Governments must increase domestic financing to over 10% as per the Abuja Declaration,” Onuh said.

She stressed that youth-led initiatives deliver measurable results. “When we invested in youth-led programmes, we saw results. Youth are not just the future but the present too.”

The Gender Equality Fund, she added, has supported 15 women-led organizations across six states, creating safe spaces for adolescent girls and young women to address HIV, TB, and malaria. But such efforts are dwarfed by funding cuts from international partners and weak government commitment.

From Kenya, Chair of The PACT and Y+ Kenya,.

Maryann Wambugu spoke on progress and persisting gaps.

“With skilled birth attenders increasing from 41% in 2003 to 89% in 2022, maternal and child health outcomes have improved, including reduced mother-to-child HIV transmission,” she said.

“Modern contraceptive use has increased and myths are less prevalent. Female genital mutilation dropped from 38% in 2003 to 15% in 2024. But this is still too high,” she warned.

Wambugu also celebrated Kenya’s increased women’s political representation, citing the appointment of Justice Martha Koome as the country’s first female Chief Justice. “We young people are not just the face of the HIV epidemic but also the force that can end it,” she stressed.

*Voices of the marginalized*

Speakers from Uganda, Nepal, Bhutan, India, and the Rohingya refugee community urged inclusion of marginalized youth.

Akintole said: “There has not been good progress for transgender people. Health and gender equality are not optional. We must ensure youth in all their diversities are included. We can no longer be ‘tokens’ in systems that exclude us.”

From Nepal, Y-PEER Nepal, Nishant Kumar

highlighted both progress and setbacks:

“Institutional deliveries have reached 79.4%, maternal mortality has dropped, and new HIV infections reduced by over 75% between 2010 and 2024. But health remains underfunded at just 4.62% of the national budget, and out-of-pocket expenditure has risen to 54.2%. Young people with disabilities face huge barriers due to lack of interpreters and inclusive services.”

Noor said refugee youth are often ignored:

“For many of us, health and wellbeing are not delayed rights but denied rights. Refugee girls grow up without knowledge of their bodies or reproductive health. Even when services exist, lack of documents and language barriers stop access. We need to be trusted as leaders of change, not just invited to share stories.”

Youth Lead Voices, India, Pooja Mishra

emphasized peer-led solutions: “Youth Lead Voices has over 1,860 young people living with HIV who are virally suppressed. We created safe spaces where young people access psychological support and build leadership skills. We must institutionalise peer-led counselling and mental health services.”

And from indigenous communities, Supriya Rai of AIYP, Nepal, said: “Youth-led mobile and community-based clinics are taking services to remote indigenous areas. Traditional healing is being integrated with biomedical care. But investment in indigenous youth mental health is critical as rates of depression and suicide rise.”

Summing up the discussions, Lead Discussant for SDG-3 at the UN High Level Political Forum 2025, Shobha Shukla, said: “Young people today are growing up in a world beset with crises, health, gender, climate, and technological violence. Not just gender equality but the human right to health needs a youth-led and youth-centric approach in all their diversities. We must not leave anyone behind.”

While the conference highlighted the struggles faced by young people, especially those in marginalized groups, it also moved the conversation toward solutions.

Experts and youth leaders agreed at the media brief that the first step is inclusion. Young people must not just be talked about but brought into the rooms where health decisions are made. This could mean creating permanent youth seats in national health councils and budget committees, as well as establishing youth-led health funds that are directly supported by government and international partners.

Education also took center stage. Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE), they argued, must be scaled up nationwide, designed with the active participation of young people, and delivered in ways that reach those in rural and underserved areas, including through digital platforms.

But education alone is not enough without strong legal backing. Delegates stressed the urgency of enforcing laws against child marriage, scrapping parental or spousal consent barriers that prevent young people from accessing health services, and reforming restrictive laws on abortion to align with global human rights standards.

Strengthening the health system itself was another recurring point. Practitioners emphasized the need to train doctors and nurses to treat young people with respect and confidentiality, expand access to primary health centers in rural communities, and ensure that mental health is fully integrated into sexual and reproductive health services, supported by peer counselors and community structures.

Finally, accountability must be non-negotiable. Governments, including Nigeria’s, were urged to collect and openly publish health data that reflects age, gender, disability, and identity. Youth-centered scorecards, experts said, could also help track how well the country is meeting global targets on health and gender equality

Taken together, these solutions create a roadmap that is both ambitious and realistic. If countries can commit to them, it could turn the tide, moving from a system where young people are marginalized, to one where they are fully recognized as partners in building a healthier future.

As global leaders set sights on 2030 SDG targets, experts warn that progress will remain uneven if youth in all their diversities are excluded.

According to Noor, “Young people are not waiting for someone to give us a voice. We already have voices. What we need is for the world to listen, and act.”